|

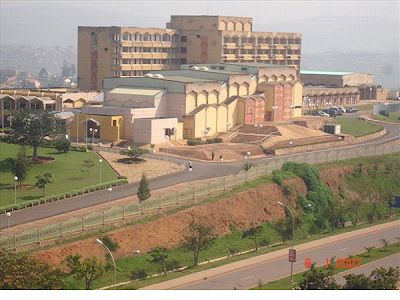

Kigali, Rwanda. It was recently named the cleanest capital city in the world by the UN. Photo by author

|

I arrived in Rwanda for the fourth time in early May to

conduct the final phase of my dissertation research on women’s political empowerment.

Kigali has changed dramatically since my last trip here in 2009—more streets

are paved, high-rise buildings dot the horizon, and the country’s impressive

economic growth is visibly apparent. Led by President Paul Kagame, Rwanda has

made

significant

progress since the 1994 genocide that devastated the country. Just last week the controversial Gacaca court system—designed to quickly and efficiently prosecute the estimated one million suspected genocide perpetrators—was declared finished. Perhaps most famously, Rwanda has been heralded for its successful promotion of gender equality and currently has the world’s highest percentage of women in Parliament (56%). While these achievements have garnered international praise, the Rwandan government is increasingly coming under scrutiny for its human rights practices, its rumored support of the bloody war in Congo, and its heavy-handed control over the daily lives of its citizens.

significant

progress since the 1994 genocide that devastated the country. Just last week the controversial Gacaca court system—designed to quickly and efficiently prosecute the estimated one million suspected genocide perpetrators—was declared finished. Perhaps most famously, Rwanda has been heralded for its successful promotion of gender equality and currently has the world’s highest percentage of women in Parliament (56%). While these achievements have garnered international praise, the Rwandan government is increasingly coming under scrutiny for its human rights practices, its rumored support of the bloody war in Congo, and its heavy-handed control over the daily lives of its citizens.

On the other hand, I’m constantly running into the appendages of a strong, authoritarian state, and finding evidence that “women’s empowerment” in Rwanda is full of contradictions and far from complete. A recent debate centered on a bill passed by Parliament that absolves criminal liability for women who get abortions under certain circumstances (such as when the pregnancy originated in rape, incest, or a forced marriage, or when the life of the mother is at risk). This highly controversial bill comes at a time when hundreds of girls in Rwanda are in jail for seeking abortions, and, according to the Ministry of Health, an estimated 60,000 abortions are conducted illegally every year—40% of which lead to medical complications that require treatment.

At the root of the abortion debate is the inconsistent

development between the core and the periphery of the country, and the tension

between implacable government regulations and the ability of ordinary citizens

to accommodate them. Millions of Rwandans have been left out of the country’s

impressive economic development. They are “stuck”—as Marc Sommers has described

them—between deeply engrained cultural expectations about marriage, sexuality,

and gender roles, and a country that is rapidly advancing and actively

promoting women’s rights. Last week a woman in her mid-twenties told me that

she couldn’t possibly go to the health center to get birth control because she is

“still a girl”—in Rwanda, you are a girl (umukobwa)

until you are married. Yet, there are 9 men for every 10 women in this country,

and housing and land shortages mean that traditional marriage expectations are increasingly

hard to fulfill. This country also has with a national health care plan that

provides free or low cost family planning resources to anyone who wants them.

My research here thus faces the challenge of balancing the various

ways in which women’s progress is understood. As I interview women in politics

and civil society organizations, I remain optimistic that the gains at the

national political level will eventually translate to progress for the masses but

I also remain unconvinced.

— Marie Berry

Marie Berry, a Ph.D. candidate in the Department of Sociology at UCLA, recently received A CSW Jean Stone Dissertation Research Fellowship. She holds an B.A. with honors from the Jackson School of International Studies at the University of Washington and an M.A. from the Department of Sociology at UCLA. Her dissertation, “From Violence to Mobilization: War, Women, and Political Empowerment in Rwanda, Bosnia, and Beyond,” explores the effects of mass violence on women’s participation in politics and community organizations in Rwanda and Bosnia-Herzegovina. In 2010 she joined the Board of Directors of Global Youth Connect, an organization that empowers youth to advance human rights through cross-cultural training programs in post-conflict countries.

Photos: Top: Kigali, Rwanda. It was recently named the cleanest capital city in the world by the UN. Photo by author Middle: 2012 meeting of the Rwandan National Women's Council attended by members of the NWC, parliamentarians, and civil society representatives. Photo courtesy of Ministry of Gender and Family Promotion 2012, Rwanda. Bottom: National Parliament, Kigali, Rwanda. The political progress in Rwanda is often juxtaposed with the memory of recent violence — here the Parliament of Rwanda, home to the highest percentage of female legislators in the world, is deliberately left damaged from artillery and grenades during the genocide 18 years ago.

No comments:

Post a Comment